Chesterfield (Cestrefeld) has both Saxon and Roman roots, from the Old English ceaster ‘Roman fort’ + feld ‘open country’.meaning ‘the open place below the camp or fortification’.

Towards the middle of the 1st century A D Romans built a fort on the sandstone spur above the junction of the marshy valleys of the Rivers Hipper and Rother. It was a staging post on Rykneld Street, the Roman road which connected Derby and Rotherham. for the transhipment of lead and wool from the Peak District. The fort went out of use in the middle of the 2nd century, but the seeds of a market town were sown.

In 955 A.D. it was known as Cesterfelda and Uhtred Child, a Saxon aeldorman. was given permission to build a bridge and town and to administer justice at Chesterfield.

In Domesday Book Chesterfield is known as Cestrefeld.

St Mary and All Saints church

It is thought that a pre-Norman church existed on the site of the present church, probably when Mercia was converted to Christianity.

It developed as a busy medieval market town outwards for about ¼ mile from the church, with the market on the level ground to the north of the church, limited in size by the steep fall of the land. About 1200 it was decided that a large new market place should be laid out to the west of the medieval town, the only direction in which there was comparatively level land easily available.

Building or ‘burgage’ plots became available along north and south sides only of this market, which encouraged the westward development of the town. In 1204 King John granted the manor of Chesterfield to William Brewer, confirming it as a ‘free’ borough with two weekly markets and an eight-day annual fair in September.

The Battle of Chesterfield was fought in 1266. It was a skirmish between Earl de Ferrers, Lord of the Manor, and troops of Henry III. Fighting took place in and around the market place until Earl de Ferrers was defeated losing his lands.

The busy market town continued to grow and thrive, in spite of a reduction in population due to the Black Death in the 14th century. The Plague again took its toll in 1586/87 but after this the town was fortunately spared further large outbreaks.

Local industries supplied the domestic needs of the townspeople; coal was obtained from small pits around the edge of the town: there were several potteries, and lace-making had some importance at one time. Tanning was carried on as early as the 13th century. Prisoners billeted in the town during the Napoleonic Wars taught a type of glove-making which continued until mid-Victorian times. Mining and smelting of lead and ironstone continued to be an important industry and there were three large breweries.

In June 1688 the Cock and Pynot (Magpie) Inn at Old Whittington, 3 miles N.E. of the town, was the secret meeting place chosen by the Earl of Devonshire and two friends for composing a document inviting William of Orange to come to England and depose James II. William accepted and the Protestant royal line was thus firmly established when the Catholic James fled to France in 1689.

The Cock and Pynot Inn became known as the Revolution House and is now a small museum. The cock and magpie have become part of Chesterfield’s coat of arms.

In 1777 Chesterfield Canal was opened, connecting the town to the River Trent, giving easier access to the rest of the country and speeding up the movement of goods. The canal was designed by James Brindley, a Derbyshire man born at Tunstead near Buxton, and an engineer of great renown.

The canal was soon superseded by the railway and in 1838 railway pioneer George Stephenson came to live at Tapton House on the outskirts of Chesterfield. He was chief engineer of the North Midland Railway Company which built the line from Leeds to Derby, through Chesterfield. He had developed the first commercially successful steam passenger locomotive and had been involved with many other successful

engineering projects. In his latter years he encouraged the spread of education through Mechanics Institutes, and experimented in horticulture. He founded the Clay Cross Company, and as the 19th century progressed, engineering became one of the principal industries in the district.

Stephenson died at Tapton House in August 1848 and is buried in Holy Trinity Church on Newbold Road.

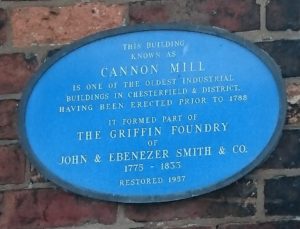

Throughout the Victorian era Chesterfield expanded as the Industrial Revolution developed. Its population had increased from 7,000 to 40,000 between 1700 and 1820 but as some industries died out, some grew in importance. About ½ mile west of the town centre was the Griffin Foundry which at one time employed well over 1,000 workmen making kitchen stoves, ranges and fireplaces of high quality in iron and steel. Cannon balls, grenades and cannon were made there during the Napoleonic Wars.

Built in 1757, Chesterfield’s largest textile works, the Silk Mill, stood on the banks of the River Hipper. Latterly it was used as a warehouse until its demolition in 1967.

Present day industries include coal mining, heavy and light engineering, tanning, glassware, chemicals, pottery, sweet-making, packaging and personal hygiene products. Staveley and Brimington were added to the Borough in 1974 and it now covers well over 16,000 acres, with a population of 100,000.

Chesterfield Crooked Spire, St Mary and All Saints, the world famous Crooked Spire Church at Chesterfield.

Construction began in the late 13 Century and was finished around 1360. It is the largest church in Derbyshire and its unusual Spire stands 228 feet from the ground and leans 9 feet 5 inches from its true centre.

At 9 a.m. on 22nd December, 1961 a fire broke out in the North Transept and flames swept through the building threatening the spire. It took two hours to get the blaze under control and the cost of the damage came to £30,000.

The Spire was ‘twisted’ when unseasoned wood was used during its construction with 32 tons of lead tiles placed on top and as the timber dried out the weight of the lead twisted the spire. As the spire was being built at the time of the Black Death in 1349, a theory has been put forward that the original craftsmen may have died. As a result, less experienced men completed the job and they made the mistake of using green timber. There is also a lack of cross bracing in the structure.

There are of course other controversial versions of how the twist was caused and the Devil figures in the most popular version although there are several variations on this theme.

One version is that a blacksmith from the nearby village made a poor job of shoeing the Devil who, lashing out in agony as he passed over Chesterfield, gave the spire a violent kick.

Another claims the Devil was resting on the spire when a whiff of incense from below made him sneeze, and as he had his tail wrapped tightly round the spire at the time this caused it to twist.

A controversial version brings the virtue of the local ladies in to question as it says that whilst resting on the spire the Devil twisted round in surprise because the bride was a virgin.

An even more slanderous version says that the spire twisted when a virgin married in the church but will straighten when another one does.

In the churchyard is an 1824 gas lamp which originally stood in the Market Place.

Old postcards of Chesterfield Crooked Spire can be seen at Old Derbyshire Postcards.

from Chesterfield Borough website –

The Town Hall is situated on Rose Hill, Chesterfield, overlooking Shentall Gardens and the War Memorial. Construction of the building commenced in 1935 and was completed in 1938. The building was designed by Mr A J Hope of Messrs, Bradshaw, Gass and Hope. The tender for the build was granted to Robert Carlyle Co. Ltd. of Manchester in June 1935. The building cost £142,500 and was opened by the Duchess of Devonshire (the present Duke’s grandmother) on 6 April 1938.

The building was designed by Mr A J Hope of Messrs, Bradshaw, Gass and Hope. The tender for the build was granted to Robert Carlyle Co. Ltd. of Manchester in June 1935. The building cost £142,500 and was opened by the Duchess of Devonshire (the present Duke’s grandmother) on 6 April 1938.

The interior has beautifully crafted walnut panelling and furniture that was specifically designed for the building even down to desks, chairs and cupboards. An Egyptian theme runs through the decoration and there are lotus flower motifs in the ceilings.

Chesterfield Market pump – Early/mid 19thc may be earlier. The well was sunk to a depth of about 11 metre. John Wesley spoke from the ‘town pump’ in 1777.

A plaque reads –

“TOWN PUMP”

The town pump was designed by local surveyor

Samuel Rollinson

It was erected in 1853 for the benefit of townsfolk and market traders.

The well was sunk to a depth of about 11 metres.

Water carts carried water from the pump to other

locations within the town.

The pump was sometimes used as a platform for public speaking.

It is now ‘listed’ as a structure of special architectural and

historic interest, grade II.

The Queen’s Park was opened in 1887 to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee.

In 1886, the then Mayor of Chesterfield proposed that a public park be created to mark Queen Victoria’s upcoming golden jubilee in 1887. However, it took the Local Government Board a further six years to agree on costs and the park was eventually opened to the public on 2 August 1893. Chesterfield Cricket Club was granted exclusive use of the ground in February 1894, and the first game was played there on 5 May 1894.

The first County Cricket match held here was between Derbyshire and Surrey, in 1898 – the same year the Cricket Pavilion was opened. In 1904, the famous cricketer WG Grace played at Queen’s Park in a match between Derbyshire and London County, and Don Bradman, the man many consider to have been the best batsman of all time, played here when the Australians toured England in the 1930s. Queen’s Park still hosts County Cricket matches today. John Hampshire, a former test batsman, called Queen’s Park ‘the loveliest ground in the country’.

In the St Mary and All Saints Crooked Spire churchyard is the first gas lamp to be erected in Chesterfield – it is dated 1824. It was first sited at the South East end of the market place and then at the junction of Packers Row and Central Pavement. It was designed by Joseph Bower. When the lamp stood in the market place it was supplied by gas produced in the cellar of a nearby shop. In 1881 there was a dispute between the Gas Company and the Council about gas prices. The gas supply was ultimately cut and subsequently Chesterfield became the first town in England to have electric street lighting.

The entrance to Chesterfield gas works can be seen on the West side of town.

There is also a plaque above where chains were drawn acrosss the road to stop traffic and allow trains to cross from the Brewery sidings the the Gas Works.